Reading the Politically Incorrect Guides

has been a journey of mixed pleasures and horrors for me. This series by the conservative,

once-libertarian Regnery Publishing house tackles various controversial subjects

either through a conservative or libertarian worldview. Some of the obviously conservative Guides often make me cringe from bad

ideas, like the highly imperialist Guide

to the British Empire or the militarist Guide

to Islam (and the Crusades). Tom

Woods’ libertarian Guide to American

History is by far my favorite.

Reading the Politically Incorrect Guides

has been a journey of mixed pleasures and horrors for me. This series by the conservative,

once-libertarian Regnery Publishing house tackles various controversial subjects

either through a conservative or libertarian worldview. Some of the obviously conservative Guides often make me cringe from bad

ideas, like the highly imperialist Guide

to the British Empire or the militarist Guide

to Islam (and the Crusades). Tom

Woods’ libertarian Guide to American

History is by far my favorite.

However, even the conservative volumes

contain a treasure trove of gems of wisdom.

Ronald Reagan, after all, said that the very essence of conservatism is

libertarianism. Dr. Elizabeth Kantor’s Politically Incorrect Guide to English and

American Literature is a new favorite which I hold in high esteem. Kantor adequately and rightly blasts leftist

interpretations of English and American literary giants, like William Shakespeare,

Jane Austen, and Mark Twain. She

destroys the modern, post-modern, and even Marxist literary theories plaguing

academia. Writes Dr. Kantor:

I don’t think there’s any need to feel like a philistine if you agree with the judgment of Cordelia and Charles in Brideshead Revisited—by Evelyn Waugh, another avant-garde [modernist] convert to the Catholic Church—that “Modern Art is all bosh.” The visual arts, especially, seemed in the modernist era to become infested with something like contempt for beauty, for the artist’s own skills, and for his audience.As Waugh insisted, real art is first and foremost the art of pleasing. It’s difficult to see why viewing the works of the Dadaists, for example—the copy of the Mona Lisa with a mustache painted on her upper lip, say, or the ordinary urinal set up in a museum as if it were a sculpture—is an aesthetic experience at all. These things attract attention for reasons that are very different from the qualities that draw people to earlier works of art, even ones as distant in time and different from one another as the Parthenon and the paintings of Monet.

I’m glad I read this book because I had

come to an independent conclusion regarding William Shakespeare and some other authors

of the later classical era. That is,

quite, plainly, that they’re reading into themes that simply aren’t there. This holds especially true for Marxist

theory, gender theory, and queer theory.

I have nothing against Marxists, gender experimenters, the LGBT

community, or the modernists and post-modernists at large (other than my opinion that their literary theories regarding

Shakespeare et. all are rubbish).

For example, there’s a lot of queer

theory surrounding the cross dressing in Shakespeare’s comedies, but I doubt

Shakespeare was “making a statement.”

Dr. Elliot Engel talks about the crude, coarse diction with which

Shakespeare wrote. Though the highly antiquated

form of "New English" sounds impressive and sophisticated to the modern ear,

Shakespeare was actually writing for the understanding of the plebeians on the

lower rungs of society. On top of his penitent

for being crude and crass, he had an affinity for sex jokes, like “My wife is

slippery” (Winter’s Tale, Act I,

Scene 2). With dilemmas like the

shepherdess Phebe falling in love with Rosalind (disguised as a man), it’s

highly reasonable to affirm that Shakespeare was not contributing to gender

theory and queer theory, but rather just making gay jokes.

While Charles Dickens and the

Bronte sisters did indeed write about injustices occurring in English society, they

weren’t blaming capitalism or white manhood or anything else the leftists like

to form ridiculous theories on. Instead

they were harshly criticizing people in positions of power and authority who

were not living up to their responsibilities of being good heads of household,

responsible for providing for and raising their children until they married

off, or who were neglecting their duties as Christians to voluntarily help the

less fortunate.

It purely annoys me, as it does Kantor,

that leftists buy completely into theories that aren’t there in order to justify

their counter-culture’s annihilation of mainstream culture and traditions. Personally, I’m a fan of Christianity, of the

idea of a warrior’s honor, and of chivalry in a man’s courtship of a

woman. I don’t deny that all men and

women are created equal in the eyes of God and that. What many never take into account, however,

is that there are major differences between the good and the bad. Christianity is not the same as Christendom—the

forceful imposition of Christianity by the state—nor is an empire justified in

waging unconstitutional war, but that doesn’t take away from the honor of a

soldier who joins up so another won’t be drafted, and who lays down his life

for his friends.

Even more importantly,

the equality of men and women under the law doesn’t make chivalry a bad thing,

especially not in the way a gentleman is supposed to treat women of all races

and classes better than himself. Hell,

if more men practiced chivalry and reintroduced it into our culture, there would

be a lot less domestic violence. If the

leftists want to live alternative lifestyles, let them—they’re adults! I just wish they didn’t feel the need to tear

down culture and tradition to make room for their counter-culture.

It’s safe to say that, beyond these

modernist and post-modernist schools of literary “thought,” modern art annoys

me greatly. I see some of these works

and most of them make absolutely no sense at all. There are many different ways one could

interpret Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” or El Greco’s “Disrobing of Christ,” but

how does one receive or interpret Yves Klein’s “Blue”? It’s just a shade of dark blue and nothing

else! Furthermore, don’t even get me

started on the vulgarity or the sheer emptiness behind “Piss Christ” (a photo

of a crucifix submerged in urine)…

Much of modern “art” pales in comparison

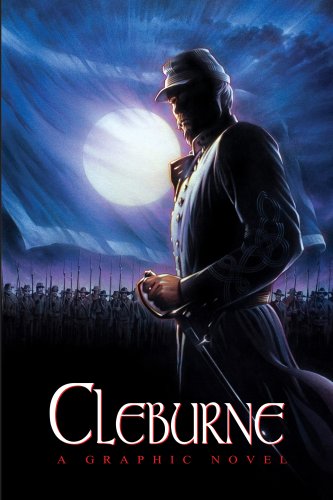

to many American comic books. One comic

book that stands head-and-shoulders above malarkey like “Piss Christ” is the

graphic novel Cleburne by Justin

Murphy. This 200-page comic book tells

the story of Patrick Cleburne, the Irish immigrant and Confederate General, in

the final year of his life. This

Confederate General could justly be considered one of the early civil rights

activists in America, regardless of what color he wore during the War Between

the States.

Much of modern “art” pales in comparison

to many American comic books. One comic

book that stands head-and-shoulders above malarkey like “Piss Christ” is the

graphic novel Cleburne by Justin

Murphy. This 200-page comic book tells

the story of Patrick Cleburne, the Irish immigrant and Confederate General, in

the final year of his life. This

Confederate General could justly be considered one of the early civil rights

activists in America, regardless of what color he wore during the War Between

the States.

Cleburne knew by 1864 that his side was

losing the war and badly needed manpower.

Cleburne wasn’t blind to the fact that the millions of slaves in the

South were a virtually untapped recruiting source that could turn the tide of

the war. He openly and passionately

lobbied the Confederate Congress to allow the enlistment of blacks in the

Confederate Army, and the Congress fought him tooth-and-nail. Cleburne had seen black men fight on his side—some

as armed bodyguards of Confederate officers and others as militiamen.

The most important thing about Cleburne’s

world view was that he was in tune with the true purpose behind the

Secessionist cause: freedom from an overly powerful central government. In stark contrast with the U.S. military, which

offered freedom to slaves after a fixed term of wartime service, Cleburne’s

plan was to grant freedom and citizenship to Southern slaves the moment they

enlisted in the Confederate Army.

Cleburne was no pushover and his

prodding pushed others to be completely honest.

He forced other officers and civil servants out of their comfort zones

when he asked the pressing question: Was this a war for white supremacy or a

war of independence? If it was a war for

white supremacy, then the cause was already lost, as the Union had already

begun to enlist black men into the armed forces. If it was a war for independence, then the

Southern nation was obligated to bring the black man to the battlefield and

give him the chance to earn his freedom and his place of honor in service to

his country.

The main theme of Cleburne is a deeply humanistic one that stresses the equality of

men of all races and social classes. The

fact that General Cleburne was simultaneously a civil rights activist and

Confederate patriot gives his life story—and this graphic novel—a rich coat of

seasoning to intrigue the reader all the more.

Tragically, most of his contemporaries chose white supremacy over

equality, even for the sake of national independence. None of that, however, changes the fact that

Patrick Cleburne was a man ahead of his time.

Another of the graphic novel’s wonderful

elements is the excellent artwork. By no

means does the artwork resemble cheesy history comics or silver-age artwork as

seen in the old Detective Comics by

D.C., or the original Marvel Comics

of the 1930s through 60s. The cover art

of Cleburne, featuring the General

standing with his hand on his saber in the light of the moon is breathtaking. The images of columns of rebel troops that

show depth, complex color schemes, and intricate shading are works of art all

in their own right. The many drawings of

black men in rebel gray standing proud with their rifles in front of St. Andrew’s

cross (the rebel battle flag) are inspiring and would make great posters to

adorn walls.

When comparing modern “art” with pop art

revolving around heroic historical figures, it quickly becomes all too clear

which is supreme. The “artist” who

conceived of “Piss Christ” intentionally stresses the ambiguity of his “work.” This is to say that there is no meaning for

his work that he can come up with, other than that he did it purely for the

shock value and to get attention!

Compare that with the following quote displayed in the Cleburne graphic

novel:

“It is said that slavery is all we are

fighting for. Even if this were true,

which we deny, it is not all our enemies are fighting for. It is merely the pretense to establish a more

centralized form of government, and to deprive us of our rights and liberties.”

—Major General Patrick R. Cleburne

So the contestants for content, poetic

license, and artistry are as follows: a “modern art masterpiece” with no

meaning or artistic value, created solely to insult Christianity, or a comic

book about an immigrant war hero’s fight for black equality in a war of

independence? I’ll take the latter.

Dr. Elizabeth Kantor could agree with me

that Cleburne is not only rich and

colorful history—it’s literature and it’s art.

Even as one who considers himself an unyielding U.S. patriot, I have

nothing but undying respect for General Patrick Cleburne and the Confederates

of all colors for whose freedom he tirelessly campaigned. Art and literature embody ideas and values,

and few works of art embody such a noble idea as this: whether it should be

under the Stars and Stripes or the Stars and Bars, let freedom ring.

* * *

Politically Incorrect Guide cover image courtesy of Barnes & Noble and is the property of Regnery Publishing. Cleburne cover image courtesy of Amazon and is the property of Rampart Press. Black Confederates artwork courtesy of CWmemory.com and is the property of Rampart Press. All three images are used in accordance with Fair Use Law.

No comments:

Post a Comment